DALLAS CHILD — When Your Child Has A Mental Illness

Beneath The Surface

Beneath The Surface

By Elaine Rogers

For Frisco mom Kristien Graffam, the frightening roller coaster ride of raising a child with a mental illness — and finding the help and treatment that is so desperately needed — started when her son was only 9. He was in the fourth grade, and she and his teacher both noticed he had become preoccupied, anxious and easily agitated. It wasn’t a sudden change, Graffam recalls, but something that seemed to escalate.

“He seemed especially worried about death and things that might hurt him,” Graffam recalls. “He was always asking about this snake or that, and whether they were poisonous. I guess he started showing a lot of obsessive compulsive behaviors.”

During a Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS) test, the anxious student spent hours repetitively writing and erasing answers. This went on all day, Graffam says, and finally the proctors took the test away. Graffam was told that the test couldn’t be scored. So she made appointments with school counselors and scheduled play therapy sessions with a psychologist. Her son was prescribed a five-week stint of intensive outpatient therapy at University Behavioral Health of Denton and diagnosed with anxiety disorder and OCD. But by summer, the diagnosis had been upgraded to severe anxiety disorder and severe depression.

Kids may lack the vocabulary, developmental abilities, skills and life experiences to explain their concerns and manage conditions as overwhelming as depression or anxiety so it comes out in other ways, like not being able to complete a test.

Kids may lack the vocabulary, developmental abilities, skills and life experiences to explain their concerns and manage conditions as overwhelming as depression or anxiety so it comes out in other ways, like not being able to complete a test.

Jodi Paul was first alerted to her son Joey’s forgetfulness and lack of retention from his concerned teacher when he was in kindergarten. Early psychological evaluations revealed issues with attention deficit disorder and anxiety, and various medications were prescribed for those issues, “with little success,” the Rowlett mom notes. In fifth grade, Joey was tested at Dallas’ June Shelton School, a private school for “learning-different students,” and the psychologist suggested that the family pursue additional psychological testing, this time with bipolar disorder in mind, but doctors quickly ruled that out completely.

“Teachers are often the first ones to notice that something is wrong and alert the family, but they don’t always know what they’re seeing,” Paul adds. “And I think doctors are very hesitant to saddle a young person with a very heavy diagnosis like bipolar. The average person takes something like 10 years to get diagnosed properly. It’s a long time for families to wait, and that’s a lot of years they can’t get back. Kids suffering from mental illness lose friendships and damage relationships along the way. There’s a lot of collateral damage as a result of this disease.”

That was true for Joey. His bipolar disorder diagnosis didn’t come until years later and only after his manic depressive mood swings and drug addiction surfaced.

While a majority of psychiatric disorders emerge before a child’s 14th birthday (according to a 2005 study supported by the National Institute of Mental Health), it can be difficult to separate the symptoms of a mental illness — impulsive behavior, aggressiveness, or extreme anxiety, for example — from the child’s character, especially when they’re really young. Parents might reason that it’s simply another phase, like waking multiple times at night was.

Mental illness is far from a one-size-fits all condition, and dual or comorbid conditions are common — meaning mental illness categories like ADHD, autism spectrum disorders and eating disorders may accompany other conditions like anxiety, depression and bipolar disorders later.

That’s how it started for Liz Allen. Warning signs started in elementary school where Liz bullied kids and experienced migraine headaches. She was classified as having ADHD, reveals her mom, MaryAnn, of Arlington (their names have been changed at their request). But there was a lot more going on inside, things Liz says she knew were wrong but that she couldn’t control. Eventually, she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Spotting Trouble

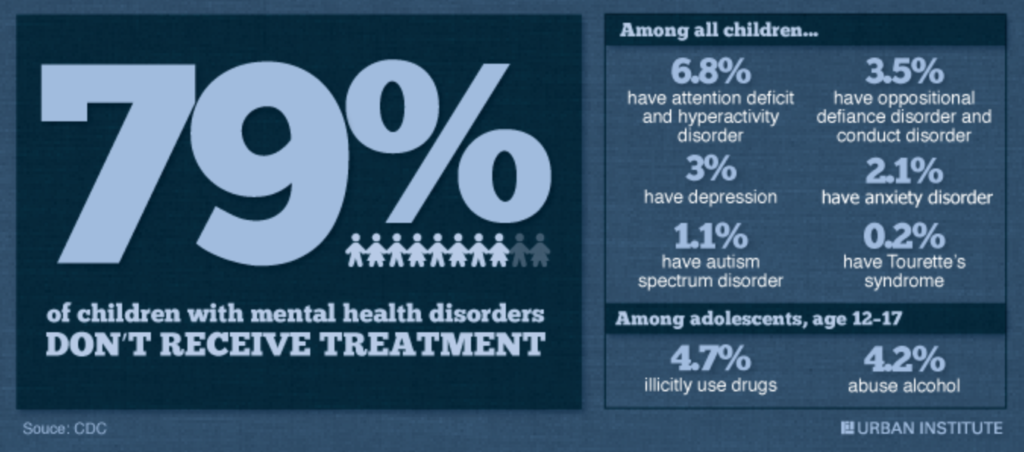

While experts say recognizing definitive symptoms of mental illness in very young children can be a challenge, Dr. Lisa Elliott, a psychologist and clinic manager for Cook Children’s Medical Center in Denton, says one in five children suffer from some sort of behavioral health illness, and symptoms can manifest as early as age 3.

“A change in behavior that lasts more than two weeks should always be investigated,” she adds.

Aside from obvious glaring red flags such as a child who hurts himself, others or an animal, for instance, parents should be aware of the following signs: separation anxiety or extreme clinginess; withdrawal; overwhelming worries and fears; an increase in headaches and stomachaches, problematic or out-of-control behaviors, inattention or irritability; difficulties with nap or bed time; excessive crying; hypersensitivity to physical contact, sudden movements or loud sounds; or a regression in previously mastered developmental skills.

“[Kids] will often have a lot more aches and pains,” Elliott explains, “plus a hypersensitivity to criticism, sleep changes, lack of energy and fatigue, difficulty concentrating and — a biggie — withdrawing from family. And there’s often a lack of enthusiasm and enjoyment and motivation to do things that they enjoyed before.”

Be aware of how these signs affect a child. Some worry is normal, especially when kids are thrust into change like moving or dealing with the loss of a grandparent, for instance. However, when worry or stress becomes persistent and interferes with their daily activities, there might be an underlying mental illness starting to surface.

And kids may exhibit symptoms of a mental illness differently than adults do. A child suffering from depression, for example, often becomes irritable instead of sad and withdrawn, like adults.

Bubbling Beneath the Surface

On the outside, Vanita Halliburton’s son Grant was well liked and smart.

“The challenge when you talk about mental health is you think you know what it looks like,” says the mom who founded the Grant Halliburton Foundation, a Dallas nonprofit dedicated to education, advocacy and support for families dealing with mental illness and suicide. “Like it’s a Cymbalta commercial and that person is going to be hiding in a dark corner wrapped in a blanket. Plenty of people are suffering with serious depression, but know how to put on a face every day and function, and kids are no exception.”

Halliburton’s foundation was inspired by her own experience parenting a child with mental illness. She launched the organization in 2005 after her son, then 19, tragically committed suicide after an extended hospitalization and treatment for bipolar disorder and psychosis.

She says it all started when Grant was 14 and showing outward signs of being a “happy-go-lucky” eighth grader while danger signals erupted internally.

“I got a call from the school counselor and she said that he was self-injuring, that he was cutting,” Halliburton remembers. “I was shocked that he would be doing something that indicated emotional pain and he was dealing with it in that way.”

The family took immediate action and got him psychiatric help, and things got better — for a while — but in 10th grade, he was skipping school, sleeping a lot and crying, all in secret.

“On the outside, his life looked golden,” his mom recalls. “He was voted teen of the Valentine’s Dance by his 1,200 peers. This did not look like a kid who was struggling, but in fact, he was struggling deeply. There’s lots of documented research now about the link between depression and highly creative, highly charismatic, highly intelligent people. In fact, some people say it almost goes hand in hand that people who have those levels of creativity and charisma actually have a predisposition to depression, so that should tell us something right there about our assumptions.”

What can and should parents do?

Parents need to slow down and pay attention. Admitting that there’s a problem is the first step. It may seem obvious, but because of the stigmas surrounding mental illness, it can be a hard thing for parents — and kids — to come to terms with. Parents shouldn’t blame themselves. While, yes, environment and relationships can affect a child’s mental state, research suggests that disorders like anxiety and depression can also stem from biological causes.

“Don’t deny it, and don’t get hung up on the label, whether it’s ADHD, anxiety or something else,” Paul advises. “Most parents dealing with this are afraid of the diagnosis, but you should go to the doctors’ appointments and learn as much as you can, as fast as you can. The most important thing is to deal with it head-on.”

A psychiatric disorder is an illness just like childhood leukemia or diabetes and requires treatment. Research shows that treatment is most successful during the first few years after symptoms appear.

Typically, teachers are the first to bring light to the dark situation, as was the case with Joey.

“The stereotypical situation with mental illness is that the behaviors become a problem at school, so that starts a family on the path for answers,” says Matt Roberts, president of Mental Health America of Greater Dallas. “Parents can get frustrated because they don’t know where to turn, and schools are limited with what they can do in terms of testing.”

Like other professionals in the mental illness field, Roberts advocates for early psychological testing whenever parents have concerns about their children’s behaviors.

“With mental illness, it’s really important to identify what you’re dealing with as early as possible,” he says. “The earlier we start treatment, the better the outcomes and the less severe symptoms might be down the road.”

Elliott suggests that any parent troubled by a child’s unusual behaviors make an appointment with the family pediatrician and other specialists such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, mental health counselor or behavioral therapist.

Besides helping families track possible comorbid diagnoses — for instance, a mix of depression and anxiety — she says psychological testing has the benefit of revealing a child’s strengths and weaknesses, which can help professionals determine effective therapies.

Communication and Treatment

Don’t let the stigmas — fear and shame — often associated with mental illness prevent you from seeking help for your child. A psychiatric disorder diagnosis isn’t a reflection of you and doesn’t necessarily mean your child is damaged for life. In fact, research shows that there’s a good chance that with the right treatment (or combination of treatments), she can develop into a healthy adult.

It’s important for parents with worries that their kids’ mood swings or irritability may be a sign of more than angst to put communication on the frontburner.

Diagnosing mental illness in children can be difficult because young children often have trouble expressing their feelings, and normal development varies so much from kid to kid.

Dr. Beth Kennard, of the Suicide Prevention and Resiliency Center (SPARC) at Children’s Health in Dallas, notes that it can be hard to distinguish whether a child’s anger or sadness might signify a deeper problem because some children hide emotions very well.

“It’s possible that the outward signs might not be there, so talk to [your kids], ask them how they’re feeling and try to be as connected as possible to them and their world,” she explains.

“It’s possible that the outward signs might not be there, so talk to [your kids], ask them how they’re feeling and try to be as connected as possible to them and their world,” she explains.

When it comes to recognizing a problem — and diagnosing it — Elliott advises staying cognizant that “this is a potential cycle” that requires being very aware and vigilant about what is going on and making sure to address everything.

“Maybe you’re doing a type of therapy and using cognitive behavioral treatment techniques, then teaching them coping tools,” she adds. “Or maybe you’re looking at medication or the option of biofeedback, plus creating school modifications. Whatever the approach, it really needs to be a holistic treatment so that child has a greater chance of success.”

Symptoms of mental disorders can change over time as the child grows so treatment options can be fluid. What works this month might not work as well in the future. As hard as it is, treating a child’s mental illness takes a tremendous amount of patience and trial-and-error experimentation with therapies and/or medications.

After Graffam was finally aware of what was going on with her son mentally, she had hopes that the well-implemented treatments the doctors suggested would produce quick and promising positive results. Not the case. When treating mental illnesses, especially in children, it can be touch-and-go.

“It’s easy to fall into a black hole of not knowing what to do and not being able to see any kind of a future when your child is struggling with this,” Graffam explains. “I just tell other parents to keep believing that it can get better. You just need to seek out support from psychologists, the schools and elsewhere, and trust yourself to find help where you can.”

Mental illness is a life-threatening disease, “but with tremendous support, it can be managed,” Paul says.